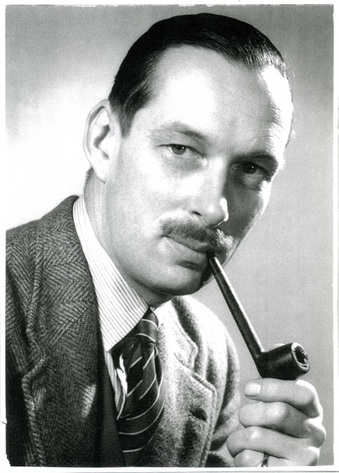

Alastair Scott Johnston

‘The Navy Lark’ became a mainstay of the 1960s radio light entertainment landscape around the globe because of the efforts and imagination of one very perceptive person: Alastair Scott Johnston.

Before we continue please note the complete absence of a hyphen between Scott and Johnston. Scott was a middle name which Alastair chose to include in order to differentiate himself from the numerous other Johnstons and Johnsons back then.

It was a simple but practical solution to avoid being confused with other employees likewise named in those post war years as more similarly aged people joined the corporation and (like every generation) certain first names were widespread.

He joined the BBC (on an impulse) having decided that a career in banking was a very unsuitable vocation. Alastair was walking past Broadcasting House one day, disillusioned with working in finance, when impulse propelled him inwards to enquire whether any job vacancies existed. Despite being advised that the application list for a particular post had closed, he managed to persuade the appointments officer to add his name to the end of the list. He sat up most of that night reading 6 plays cover to cover, and when interviewed was able to eclipse the panel’s working knowledge of those particular texts. His knowledge and enthusiasm inspired the interviewers, who duly appointed him.

His early days in radio included the job best described as ‘effects boy’, with responsibility for finding and producing extraneous sounds/music for various productions. Alastair was very much a typical BBC career man. He loved working in light entertainment and was never happier than when crafting and honing his many shows.

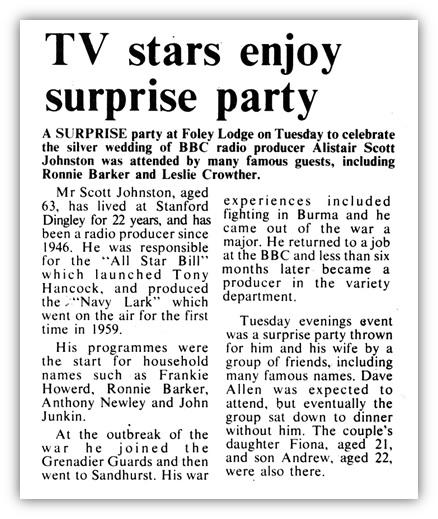

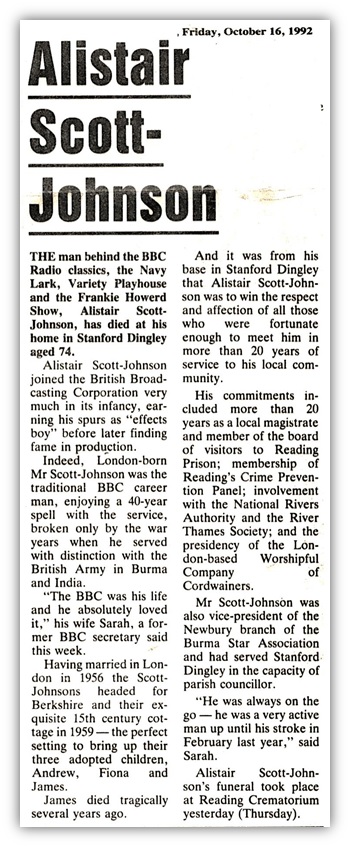

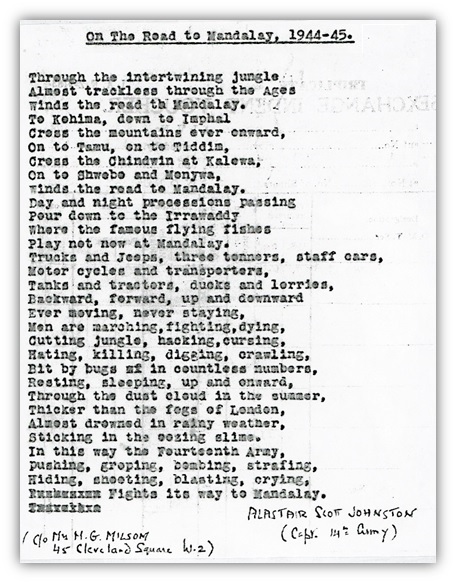

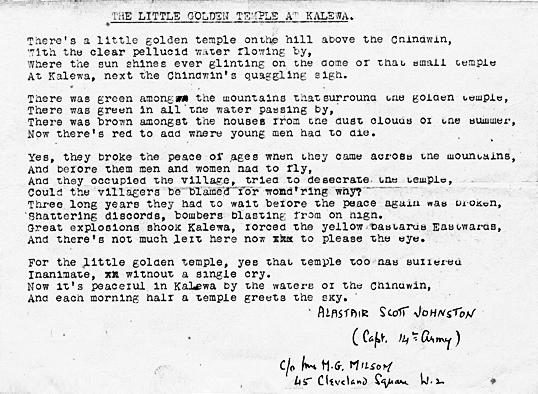

The 1939-45 World War interrupted Alastair’s career in broadcasting. His army record shows that he served with distinction in Burma and India. Upon returning to the BBC and his radio based career after the war, he became a producer in the variety department after just 6 months tenure (1946). Alastair worked in the midst of such notables as Henry Hall. Early successes such as ‘All Star Bill’ launched Tony Hancock, Frankie Howerd, Anthony Newley, Ronnie Barker and even Semprini. Entertainment shows under his supervision evolved into ‘Variety Playhouse’, ‘The Floggits’ and a host of well-loved shows. Despite being a very busy person he kept a diary for his entire life, in which he carefully chronicled his professional life. Using the entries from this primary source, we can quickly separate fact from fiction, especially where ‘The Navy Lark’ is concerned.

A common misconception was that ‘The Navy Lark’ was meant to be a vehicle for Jon Pertwee, a frequently quoted remark but without any substance. Laurie Wyman (he later revised the spelling to Lawrie) wrote a synopsis for a programme and took it to Alastair Scott Johnston; at this point it was actually not written for any particular service, but as Scott Johnston was from an army background and Laurie Wyman had served in the air force they decided to split the difference and agreed on the ‘The Navy Lark’, so neither of them would have the upper hand with regard to protocol or experience.

The idea of a ‘services’ Lark came from Laurie in conversation. The original script he drafted in November 1958 fell well short of Alastair’s expectations and he completely rewrote it in order to provide a clearer ensemble situation comedy with wider opportunities to develop different plots which helped Lawrie conjure realistic storylines based both on ward room gossip and a great imagination. He is also on record as saying that ‘Jolly Jack Tar could be forgiven anything because of his conditions of service (being stuck in a boat for long periods of time) whereas soldiers or airman would not be forgiven for making such silly or huge mistakes!’ An interesting point to note is that Alastair Scott Johnston, uniquely, had complete casting rights to all the shows he produced.

There were four Larks in all: ‘The Navy Lark’, ‘The TV Lark’, ‘The Embassy Lark’ and right at the end of the sixties ‘The Big Business Lark’. It is believed that a further sister show called ‘The Ministry Lark’ was suggested to the Head of Light Entertainment at the BBC but was turned down. Curiously within a year the network scheduled ‘The Men From the Ministry’ (1962-1977)- coincidence? However, there is no mention of this in Alastair’s diaries, and Mrs. Scott Johnston also confirmed that she has no recollection of the show ever being seriously considered. Although Alastair may have discussed the possibility with Laurie Wyman, he worked more with writers John Junkin and Terry Nation (pre Dr. Who) with whom he had frequent ‘Think-Tanks’ - as they called them – for new shows. ‘The Embassy Lark’ arrived complete with fanfare and enjoyed three seasons sharing cast members from ‘The Navy Lark’ and storylines about a fictitious island and the various rivalry and kinship between different ambassadors on Tratvia from 1966 to 1968. It is probably pertinent to note that exactly the same concept was reinterpreted by Alex Shearer in ‘Flying the Flag’ also featuring a British embassy in the Eastern Bloc (like Tratvia) during the Cold War. It aired twenty years after ‘The Embassy Lark’ and ran for four series, aired from 1987 to 1992.

It is very evident that Alastair evoked tremendous loyalty and a phenomenal team spirit amongst his colleagues in front of and behind the microphone. Evelyn Wells was Alastair Scott Johnston’s secretary for over 15 years, and attests to the professionalism and care that personified Alastair’s work and philosophy. Evelyn was invariably present at those Sunday recording sessions, always ready to type an extra script (no photocopiers in those days) or help out wherever needed, including keeping the younger members of the production team's families well nourished!

Most of the later ‘Navy Larks’ were recorded at The Playhouse. The first point of call for the cast when arriving was the canteen. Once inside, the fortnightly routine of the production team varied little: a tortuous journey up three floors in a very old rickety lift which shuddered along, its occupants eventually being delivered to the canteen where the cast enjoyed several cups of coffee and ‘sticky buns’ and caught up on the gossip from the previous fortnight. This was followed by a procession down to the studio for the serious work of rehearsing two episodes between 3 and 6pm. An order for more refreshments was ALWAYS made for about 6pm! This practice continued right up until the final recording of ‘The Navy Lark’ at the Paris Studio in 1977.

Prior to the live recording, Alastair would be given a list of coach parties so he could welcome them . He always did the warm-up chat, which varied little. He would explain studio management, recording technicalities, what the microphones hanging from the ceiling were for and so on. To one side of The Playhouse stage was a statue of a naked lady whose breasts he always covered with his hanky during one of his jokes. Jon Pertwee is known to have retold this story and mistakenly attributes the gag to himself, but it was part of Alastair’s regular warm-up routine. He also used to warn an unsuspecting member of the audience in the front row that they might well have to give up their seat as a blind gentleman was in the habit of attending the recordings and usually sat on it. There was, of course, no such person. Two shows were always recorded consecutively, starting at 7pm on a Sunday. This meant that the earliest the studio emptied was around nine o'clock; it was then a quick dash around the corner to the pub in time for last orders!

To be present at one of Alastair’s recordings was a fascinating experience. If there was a technical error, or the cue light did not come on at the right time, or if a sound effect was not right, the whole scene would have to be re-recorded. Despite the inevitable repetition, the audience always managed to laugh in exactly the same place even though they had already heard the joke. We are still laughing at those wonderful lines today, even though we have heard them many times before. Praise and credit must go to the entire production team and cast for their commitment and talent in producing such a marvellous show, and in particular to Alastair Scott Johnston for his enduring comedic legacy.

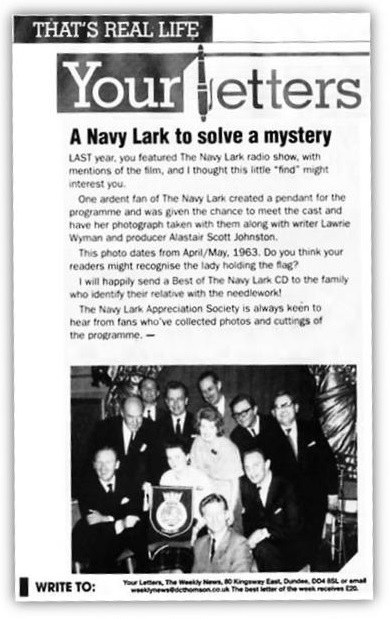

A photograph (from Alastair’s own archive) taken with the cast and himself after a recording of ‘The TV Lark’/‘Navy Lark’ S5 in The Playhouse with a fan who had created a highly detailed embroidered banner. Despite our best efforts we have yet to be able to identify the person holding the pendant. All the usual cast members are there except Heather Chasen who was in Broadway at the time with the long running play ‘A Severed Head’ so the cast was then augmented by Janet Brown.

Another photograph from Alastair’s personal collection of performers he worked with and admired.

Many years ago I removed a comment that Alastair was a ‘Sir’ as well as that mischievous hyphen which invariably appears between the Scott and Johnston in all too many documents. However, I learned during one of my delightful chats with Alastair’s daughter that he WAS knighted: to prove the fact, she has a photo of her dad at the Palace with his award. When at the Palace getting his ‘K’ he was at the front of the queue and it was actually the Queen who knighted him. Then you are supposed to step back about 5 paces and bow. Alastair said, ‘Thank you’, walked back to his seat, sat down and there was a big rip noise followed by her father jumping up and exclaiming ‘Gawd! I split ‘em’. It was noted that had he stayed quiet no one would have known because he was wearing a morning tail coat jacket! However, Alastair had an intense dislike for everyone he ever encountered who had been likewise ennobled and decided that he would never acknowledge the accolade in any way. Whenever the press or friends asked him if he had a gong he would say ‘No’.

This misdirection went on throughout his life, despite his very frequent visits to the Palace. Only once did he admit to being a ‘Sir’, after being pressed on the matter when asked to supply information to the authorities relating to his personal status. The awkward situation began with his initial denial, then embarrassed acknowledgement of the hidden truth about his award. Despite this event, he continued to maintain his ‘Mr’ title throughout his life.

Two poems published whilst Alastair was still in uniform. The first was typed on the back of an internal blank invoice and the second on a piece of available manila paper.

Text © Fred Vintner, 2021.